The Reactor

When everyone is Mozart, who'll be the audience?

I first met Julian at Hanson’s.

That’s what everyone called it—just Hanson’s, like it was some kind of weekend retreat.

The journey there was uneventful. The shuttle had been silent except for compliance pings and the hum of climate regulation. Two hours north of what used to be Phoenix, through reclaimed desert.

The ranch itself was beige buildings against a washed-out blue sky, the air faintly antiseptic. My roommate had already claimed the better bed. I didn’t care. I set my things down and stared at the wall, that particular shade of institutional beige that somehow made you feel both calm and erased.

When I made my way to the common room, he was there—a tall man folded into a low-slung chair, his fingers conducting a phantom orchestra on his knee. The gesture was unconscious, carved so deep it persisted even here.

This was Julian. The Julian. The man whose reaction to the Berlin Philharmonic’s final live performance had been inducted into the Cultural Archive as a standalone work of art. People called him the Stradivarius of expressiveness—not the maker, but the instrument. Music moved through Julian and came out transformed, elevated. At his peak, he didn’t just witness art; he amplified it.

And he was here, in the same mid-tier facility as me.

He must have felt my stare. His eyes met mine, and for a fraction of a second I saw the man from the feeds—that absorbing focus that had thrilled me so much as a teenager. Then it vanished. He gave a slight nod.

The irony wasn’t lost on me. I’d been using that same nod for months, that little gesture of validation when I couldn’t feel anything real. Now here was Julian, doing it back to me like a king acknowledging a fellow prisoner.

If Julian—the Stradivarius, the legend, the man whose capacity had seemed infinite—if he was here using the same broken techniques I was, then this place wasn’t about healing. It was a harbour where shipwrecked titans and minor leaguers like me could huddle together, pretending the cold wasn’t coming for us all.

The first group session was the next morning. Dr. Evans ran the place with the weary air of a mechanic who’d long since stopped believing he could fix engines, only replace parts. His biometric display was visible on his wrist—therapeutic transparency, though I suspected he’d learned to game his numbers years ago.

Music played softly in the background—algorithmically composed, perfect and delicate. The kind of music I used to love, once. Music used to burrow its way into me, bypassing my filters, straight to my gut—or my heart. Or my groin. Now any music I heard was just... there. I registered it the way you’d note good lighting or comfortable temperature.

“We’ll start with names, mediums, and, if you’re comfortable, what you’re struggling to access.”

Kara went first, a woman in her forties who was dressed as if she was attending a corporate mixer. “Romance literature. The swoon.” She smiled tightly. “I know what the author wants me to feel. Usually, I do. I follow the story, sense the tension, expect the ending. That part’s fine. But the swoon—that moment where you’re supposed to be swept away, heart pounding—I just can’t get there anymore. I see it’s there, but I can’t reach it. I want that back. Just that.”

Someone else—Marcus, I think—spoke about film. “Comedy,” he said. “Comedy’s my problem. I get the jokes. I see why something’s funny, know when a line lands, and can time it right. It works in my head. But the real laugh—the one that fills a room? That’s what I’m trying to find.”

I watched Julian as others spoke. He sat perfectly still, but his fingers kept moving on his knee, conducting something only he could hear.

When it came to him, he simply said: “Julian. Classical music. The crescendo.”

The room went quiet. That forward lean, the widening eyes—everyone knew who he was. The Julian was here, so broken that he couldn’t even feel a climax.

Dr. Evans leaned back after we’d finished. He’d told this story hundreds of times, but he still tried. “I want you to remember something. You chose a profession that commodified one of the last authentically scarce resources: human aesthetic attention.”

He gestured around the circle. “In an age where creation is essentially free—where anyone can generate beautiful, accomplished art with AI assistance, where lots of people choose cultural production as their primary mandatory pro-social activity—you offered something irreplaceable. The experience of being genuinely moved. You weren’t critics. You weren’t teachers. You were something much more important: you were witnesses.”

Kara laughed, bitter. “Past tense.”

“Perhaps,” Evans said. “But understanding what you were providing is the first step to understanding what you’ve lost. That capacity for care—that’s what we’re here to try to restore.”

He looked around the circle. “We live in what some people call the age of universal cultural production. In earlier times, there were gatekeepers—critics, curators, academics who decided what art got made, what art people got to see, what art mattered.

When AI made creation accessible to everyone, the gatekeepers couldn’t keep up; algorithms do that work now. But people still need validation. Algorithmic feedback doesn’t make you feel seen. That’s where you came in: the human reactor, paid to spend finite attention on infinite art.”

No one looked convinced. I was thinking about my rent, which was late. And whether they’d have the chicken again for dinner, which was somehow both overcooked and cold the night before.

I found Julian on the patio that evening, staring at the hazy sunset. The automated irrigation system hissed in the distance. I almost didn’t approach, but he spoke without turning.

“The nod,” he said. “Good technique. Reassuring. Shows you’re paying attention.”

I froze. “It’s becoming automatic.”

He finally looked at me, and that weary recognition was back. “They all do. The sigh, the smile, the nod. Masks we wear to hide a lack of genuine feeling.” He gestured to the empty chair beside him. “Don’t worry. I’m not judging anyone’s technique.”

I sat. We watched the sky bleed from orange to purple in silence. A cargo drone hummed past, navigation lights blinking in precise rhythm. As authentic as any shared experience I’ve had—two people, silent, watching the dusk settle in. No response required.

“You know what’s strange?” Julian said eventually. “When I started, it felt like a calling. I thought I was helping people connect to their own work in ways the machines couldn’t.”

He gestured at the sky, the ranch, everything beyond. “Now there are more symphonies uploaded daily than anyone could hear in a lifetime. All masterpieces: emotionally rich, heartfelt, profound. People make them for their Index, to keep receiving the UBI. The algorithms hear them, of course, but that only counts for so much. People still want to feel seen.”

“That’s what we sold,” he continued, quieter. “The validation of being witnessed—by someone who chose to spend their finite attention on your work.” He turned abruptly and looked me in the eye. “So what are you in for? Really.”

“Well, I used to think I was good. Not as good as you—but people liked my reactions, gave me encouragement. I won a few regional competitions, got some well-paying gigs.”

“But?”

“But mostly I was just performing connection. I’d study the AI analysis and translate it into human language, add warmth, make them feel special. But it wasn’t real. It was customer service with better branding.”

Julian was quiet for a long time. When he finally spoke, his voice was different. Smaller. “It used to come naturally to me. If you’d told me when I was your age that I would end up in a place like this I would have laughed at you.” He didn’t look like he wanted to laugh.

“I’ve had a long career, for this game. I once reacted to a piece by the King of England—did you know that?” His eyes searched mine for acknowledgment, then darted off into the distance, as if there was something fascinating there that he couldn’t look away from. “But nothing compared to Berlin. I was never as good before or since—it was my Everest.”

I tensed up when Julian mentioned Berlin. Everyone had heard of it—the performance that made him legendary, the crowning moment of his career.

“They tuned everything for me,” he said.

“Lighting, acoustics, even the temperature of the hall. I was the audience. The sensor rig caught every breath, every pulse shift, every micro-expression.”

He leaned back, hands resting lightly on his knees. “And I was moved. God, I was. The music came through me like glass. The strings, brass, woodwinds—they didn’t just play; they spoke. The violin solo was like leaning into light. I felt it everywhere. It was pure, overwhelming—the truest thing I’ve ever known.”

He paused, gaze drifting toward the floor. “Afterward, there was this half-second where I caught myself thinking about phrasing, about the timing. Just a flicker of measurement. I ignored it, but it was the first tremor—the start of everything coming apart.”

“My god,” I muttered. I was moved—and a little flattered that Julian was opening up to me.

“From then…it got harder. Gradually. At first there were still good days, lots of them—great days, even. But every so often I’d be reacting to a performance and suddenly find myself counting measures, analysing technique. Appreciating it intellectually but not feeling it. Just a momentary lapse of concentration, I thought. At first.” His fingers moved on his knee again until he caught himself and stopped, suddenly self-conscious. “I thought I could turn it around with sensory deprivation, rest, preparation—the usual things. Thought I could fix it. Kidded myself.”

“When did you know something was really wrong?”

“Three years ago. The composer was a nice lady from Jakarta—earnest, talented. Put everything into it. And there was this crescendo in the second movement, this swell that should have destroyed me. Should have been transcendent.” He stopped. “It was, I wasn’t. I heard the volume rise, saw the strings vibrating, the conductor’s hands shaking. I felt the pressure on my chest.” He looked at his shoes. “On me, not in me. I covered pretty well but…” His voice trailed away.

“That’s why you said ‘the crescendo’ in therapy,” I said quietly.

He nodded. “It’s not that I can’t feel anything. I still have moments. But they’re rare now, and I can never tell if they’re real or if I’m just performing what I remember feeling used to be like. The worst part is the good days. When you think maybe it’s coming back, maybe you’re healing. Then you have three bad weeks and realise—no, it’s just getting worse in fits and starts.”

“Does anyone else know? How bad it is?”

“Not really. You maintain the appearance. Take fewer gigs, claim you’re being selective. But everyone in this industry knows what selective means.” He gave a hollow laugh.

I wanted to say something comforting, something profound. Instead I said: “I’m sorry.”

“Don’t be,” he said. “Berlin was the real thing. I had that. Most people never touch something that pure, not even once. The fact that I can’t get back to it... well. At least I know what I’m mourning.”

He stood, stretched. “The tragedy isn’t that I lost it. It’s that there’s so much art in the world now—more than any civilisation has ever produced—and none of us can feel it anymore.”

“We’re buried in masterpieces.”

He went inside. I stayed on the patio, watching the sky fade to black, and for a moment—just a moment—I felt something like grief. Real grief, I thought. Then wondered if I was just performing what grief used to feel like.

Hanson’s didn’t fix me, not really. But it gave me enough to function. I learned to feel in smaller doses, to ration my attention, to come to terms with the limited capacity I’d been blessed with. I left after three weeks with a list of maintenance strategies, knowing this was the best I’d ever be. Knowing that I needed to find another profession.

Julian left a week before I did. We exchanged contact protocols—a gesture that felt both meaningful and empty. I never used mine. I don’t know if he used his.

I found work doing curation instead of reaction—matching art to audiences, designing aesthetic experiences for corporate events. It required less of me, suited me better. Less feeling, more analysis. I could do it without faking.

I met someone who worked in algorithmic curation and understood the attention economy from the supply side. We built a life where art was pleasant background noise, not the central frequency. We consumed what our feeds supplied and attended enough of the right social events to keep our Indices clean.

It was comfortable. I kept up the maintenance routines from Hanson’s: limited exposure, emotional rationing, strict boundaries. Once, early on, my partner played me something they were excited about—an opera some friend had composed—and I felt that familiar nod starting, that professional gesture of validation. I caught myself, stopped. We never talked about it.

I mostly forgot about the man who could make you hear a symphony through his silence, even as I curated experiences no one would remember.

Fifteen years vanished the way comfortable years do: quickly, without edges.

I heard snippets occasionally. Julian had taken a few more gigs. Then gone silent. Then resurfaced doing lower-tier work—hobbyist composers, vanity projects, corporate events where someone wanted the prestige of “a real reactor” without caring about the quality of the reaction.

I didn’t investigate. Didn’t want to know if recovery had been temporary, if Hanson’s had just delayed the inevitable.

Then a notification surfaced from archived data: Hanson’s servers were being decommissioned. Client records scheduled for purging. Standard data maintenance. It felt like a ghost tapping my shoulder.

I don’t know why I searched for him. Maybe it was guilt over never using that contact protocol. Maybe I wanted to know how the story ended. Maybe after fifteen years of comfortable numbness, I wanted to feel something, even if it was just melancholy.

After a cautious exchange, Julian invited me to visit.

The transit took two hours. I watched the landscape change through the window—managed zones giving way to older infrastructure that barely worked. By the time I arrived, the sun was setting. That same washed-out orange bleeding into purple I remembered from Hanson’s.

The building was standard UBI architecture: efficient, maintained, anonymous. Julian answered the door—older, thinner, the lines on his face deeper. But his eyes were clear. Not happy, not sad. Just clear.

“I wondered if you’d come,” he said.

The small living space was spartan: a single chair, a neatly made bed, surfaces wiped clean. It was the room of a man who had pared his physical life down to the essentials. Julian himself looked calm, grounded. He gestured to the second chair. “I’m glad you did,” he said, and I believed it.

We sat for a moment in comfortable silence. Then I said, carefully: “So... how have you been? Since Hanson’s?”

Julian gave a slight smile, as if he knew exactly what I was really asking. “I don’t react to music anymore,” he said, his voice even. “No point in it.” He tapped his temple. “I only compose it now.”

He must have seen something in my expression - confusion, maybe, or pity - because he leaned forward slightly. “Would you like to see?”

Before I could answer, he slid a thin neural-interface headset across the table. “It’s keyed for guest access. Just put it on.”

I hesitated, then fitted the sleek band around my head.

The room vanished.

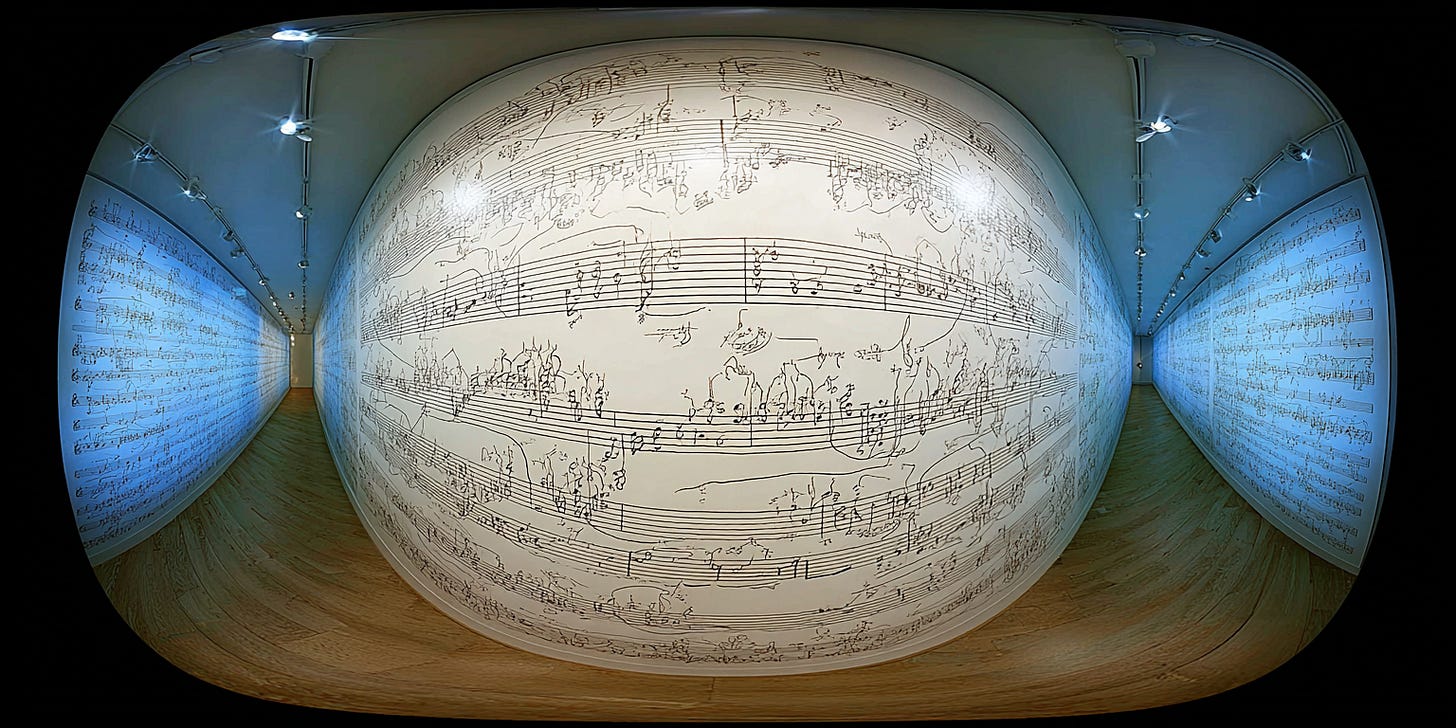

I was standing in a vast digital workspace—Julian’s workspace. It stretched in every direction, organised in layers and sections my mind struggled to parse. Thousands of musical scores floated in three-dimensional arrays, each one annotated, revised, cross-referenced. Notes tagged with emotional intentions: despair giving way to acceptance, the moment hope returns, half-remembered joy. Structural diagrams showed harmonic progressions mapped like emotional journeys. Waveforms pulsed gently, each marked with the feeling Julian had tried to capture. Some areas held competing versions of the same movement—variations arranged side by side, dozens of them, each exploring a different way to express the same truth.

The notation was everywhere. Bars and clefs and tempo markings, some in classical form, others in formats I didn’t recognise. But woven through all of it were Julian’s artistic choices—his voice, his heart. Movements from symphonies arranged spatially around central themes. A four-hour orchestral work about grief, each section meticulously crafted to express something genuine and specific. Concertos in various stages of completion, each one reaching for something beautiful and true. Revisions upon revisions, building outward like coral. Every piece marked with what he wanted to say, the human experience he was trying to capture.

It went on and on. Years of work, maybe decades. All of it organised, labelled, preserved. Not chaos—the opposite. It was methodical, purposeful, the product of sustained and solitary labour. Exquisite work. Profound work. Sophisticated, open-hearted. Work that no one had heard. The only sound was my own breathing.

I pulled the headset off.

It took a few seconds to readjust. The silent, tidy room felt smaller now. Julian was watching me, his expression calm.

“Years of composition,” he said quietly. “Every decision, every inflection, mine. Every note.” Our eyes met, and for a terrible second I saw a ghost of the eager man from the Berlin feed, unguarded and hopeful. “I’m working on a string quartet—I think it might be my best yet. Want to hear it?”

The question was so simple. Twenty minutes, maybe thirty. All I had to do was say yes. Sit. Listen. Give him what he’d given thousands—the gift of attention, of mattering to another consciousness.

But I couldn’t.

My stomach hurt. Not metaphorically—I felt it twist, that specific nausea of social anxiety when you know you’re about to disappoint someone who doesn’t deserve it. I looked at Julian, at the eager vulnerability in his face, and I knew with absolute certainty that sitting through his quartet would be unbearable. Not because it would be bad—it would be good, of course it would. He’d poured himself into every one of those pieces. That made it worse: I’d have to react, and I didn’t know if I still could. Didn’t know if I’d be faking it, couldn’t trust my own responses anymore.

And beneath that, sharper: if this could happen to Julian—the most gifted reactor of our generation—then what hope was there for the rest of us? The disease wasn’t his. It was the world’s. Too much quality. Too much abundance. We were drowning in beauty we couldn’t feel, and he was proof of where we would all end up.

A part of me wanted to stay, but I glanced at my wrist. Nothing urgent on the display, but it gave me an excuse. “Julian, I... I’d love to, but I have a thing. I’m already late.”

The light in his eyes didn’t go out; it just receded.

This wasn’t new; maybe he saw it often. Everyone who came—if anyone came—said the same thing.

“Of course,” he said. His voice was even. “Of course you do.”

I left quickly. The door hissed shut behind me. A seal on a tomb.

The elevator descended in sterile quiet.

I had refused to listen. In a world where everyone could generate their own flawless masterpiece—a new Beethoven’s Fifth every week—where AI had removed every barrier—the real scarcity wasn’t creation. It was attention. It was witnessing.

And it struck me: there must be millions of people like Julian all over the world. Composers, poets, filmmakers—all building perfect worlds no one will ever enter. Vault after vault of unplayed symphonies, unread novels, unwatched films—art profound enough to break a heart, if there was anyone who cared enough to listen. Anyone who could feel it the way people once did.

And I had looked at Julian’s vulnerability and chosen comfort.

The elevator opened. Transit was waiting. I boarded, found a seat, watched the managed landscape blur past in the gathering dark.

For all I know, he’s still there, in that small room, polishing his latest quartet. Still asking anyone who stops by: Want to hear it?

And I suspect everyone turns away.

My favorite moment was feeling the shift from "I wondered if you'd come." to "I'm glad you did." Showing that he was able to find emotion after all, through creation. This is so brilliant.

Such a poignant piece for this platform, this audience. Its not a plea but a warning. Well done.